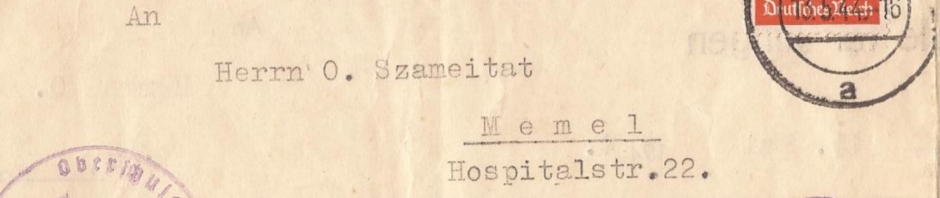

Long time readers of this blog will remember reading here that my great-grandfather, Oskar Szameitat, was arrested by the Gestapo in February 1941 and held in solitary confinement in Tilsit until December 1942 without having been put on trial at any point. After he was released, he was not allowed to return to his job as a Kriminalpolizist (police detective) and on 2nd August 1943 had his civil servant status nullified by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office). Among other things, this meant that he lost any right to claiming a civil servant’s pension, and this was a problem for my great-grandmother Johanne after the war, because she had been claiming a widow’s pension as her income for a decade or so before the West German authorities got wind of it in 1958. She then had an uphill struggle proving legally that he had been unfairly dismissed from office in 1943 so that she could continue receiving it. To do this, she had to prove that the grounds on which he was arrested and imprisoned were unfair. Over the next (probably) four blog posts, I’m going to delve into the details of what can be learnt from Johanne’s documents about the reasons for Oskar’s arrest and imprisonment. It has become clear to me over the years that the documents are incomplete, and there will be much as yet unknown detail lurking in German and Lithuanian archives that I do not currently have access to: I hope to supplement my findings one day with any additional information I manage to procure from more official channels.

It has also become clear to me as I have got more familiar with the documents that Johanne herself, at least initially, did not know into the 1950s why her husband had been detained by the Gestapo. She may well have had her suspicions, but it is clear that Oskar never told her after his release, almost certainly to protect her and the family. It seems that a condition of his release was that he was forbidden from discussing the matter. However, it does seem that he spoke in confidence to a colleague or two about some aspects of his imprisonment, including Gustav Isenheim, one of his comrades in the Küstenhilfswehr, alongside whom he was guarding the municipal water works when he died and who wrote to Johanne a few times with details of his death.

It was probably the authorities that made Johanne aware of the paper trail about Oskar in the Berlin Document Center, which housed a collection of documents from the recent Nazi past. According to the Nazi central card index, Oskar had been excluded from the party on 17th June 1941 (coincidentally (or perhaps not?) his 44th birthday), because, it had been discovered, he had “demonstrably” and “by his own admission” worked for the Lithuanian intelligence service while being a civil servant of the autonomous Memelland in the 1930s. He then appealed the decision at several levels in the party apparatus, saying that he had had to work with the (Lithuanian) state security police force for professional reasons but had always stood up for German interests in the region. At the level of the Gau, the initial injunction barring him from party membership was overturned, with the court pointing out that he had worked for the Lithuanian intelligence service before he had become a party member, but (as far as I can tell) confirmed his dismissal from the party. The deputy Gauleiter (according to this website a chap by the name of Ferdinand Großherr) raised an objection to this, and made an application for his ejection from the party, and the Oberstes Parteigericht (the Supreme Party Court) overturned the dismissal ruled by the Gaugericht. There seems to have been a (legal?) difference between whether one was excluded, dismissed, or ejected from the party, but the point remains that he was no longer allowed to be an NSDAP member, though not for lack of trying. However, usefully for me, the evidence that the Oberstes Parteigericht was basing its judgment on was also listed in the same document and boils down to the following: the Gestapo had come across information that Oskar had worked as an agent for the Lithuanian intelligence service from autumn 1932 to July 1934, being paid between 50 and 60 litas monthly for his endeavours. Apparently Oskar had admitted that his information was not very useful and he had therefore been dropped as an agent by the Lithuanians. Preliminary SS and police court proceedings into potential treason were taken up but then shelved by order of the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office) on 24th October 1942. This was apparently because legal advice had indicated that a successful prosecution was in no way possible owing to a lack of detail concerning the contents of the information that Oskar had supposedly handed over to the Lithuanians.

There are several questions that need to be addressed on reading this document. Firstly, was it true? Was Oskar an agent for the Lithuanian intelligence service in the 1930s? If so, why did this lead to his arrest (given that at the time he was a Lithuanian citizen living in Lithuania)? In addition, while Oskar’s ejection from the party certainly occurred as a result of the accusation of being an agent for the Lithuanians, did that necessarily mean that it was the reason for his arrest and detention? I’m going to park the first question for now, as it probably deserves its own blog post. But the second question can probably be answered: it certainly seems to be the case, given that initial proceedings were taken up via a court and because the document also goes on to state that the RSHA issued a decree nullifying his 1939 appointment to the post of Kriminalsekretär (detective sergeant) of the German Empire in addition to sacking him from his job for life, showing that it was not just his party membership that was at stake here.

It was certainly the case that there were a good number of agents of German ethnicity (whatever that meant, as identities were certainly fluid in that region) that were spying on German groups in the Memelland for the Lithuanian intelligence services during the 1930s. The time period in which Oskar is supposed to have been active, 1932-1934, is exactly in the ‘culture war’ window when the Lithuanians in Kaunas were getting jittery about the pro-Nazi (and therefore pro-German) mood growing among the Memelländers in their autonomous region, at the time of the so-called Böttcher affair (that’ll have to wait for another blog post), the founding of and then the banning by the Lithuanian authorities of the two competing Nazi-imitating parties, and the imprisonment of many leading Germans at the hands of the (Lithuanian) authorities on suspicion of planning an armed insurrection (see this blog post for more on the cultural and historical background of the time). The Lithuanian authorities were keen to have inside information from as many sources as possible.

Nikžentaitis (1996) draws historians’ attention to little known archival material that is now in the Lithuanian State Central Archive concerning (German) trial documents from the early 1940s of former Lithuanian agents in the Memel Territory, and gives a few examples of undercover work carried out. For example, an agent by the name of Theodor Hertel, a merchant from Memel, intercepted a letter sent to the School Councillor Richard Meyer in which receipt of an (illegal) gift of 10,000 Reichsmark from official German sources via the Deutsche Stiftung to the Memel Germans was confirmed. Hertel tried to sell it to the Lithuanian authorities so that it could potentially be used as a bargaining chip at the League of Nations (and it was indeed used to bring about German concessions) (Nikžentaitis 1996, 775).

Jakubavičienė (2012, 231) also makes mention of (presumably the same) collection of documents in the Lithuanian Central State Archives (Fond 1173) that contains over a hundred investigation reports of agents working for the Lithuanian authorities in the interwar period, some of whom, such as Max Schneidereit and Adam Mollinus, had provided information that had in part led to the mass arrests that brought about the so-called ‘Kaunas trial’ in 1934-5, sometimes referred to as the Neumann-Sass Trial, after the names of the two leaders of the Nazi-emulating parties in Memel. Now, this trial is relevant to Oskar, and I will go into detail about it in the second part in this mini-series, but all that matters for now is that I do not know whether Oskar and his case is featured in this archive, and it is on my list of things to follow up. I suspect he isn’t, for reasons that will become clear later. For those of you who speak German and are interested in the machinations of such agents, have a listen to this great radio drama from Deutschlandfunk which charts the life of Adam Mollinus.

Let us suppose for now that Oskar had worked for the Lithuanian intelligence service in 1930s and this was apparently why he was arrested, imprisoned and thrown out of the NSDAP in 1941. I do not however understand how he can have had a case to answer for: he was accused of treason against Germany, but at the time of his supposed crime, he was a Lithuanian citizen living in an (admittedly autonomous) region of Lithuania. Treason in German is Landesverrat, specifically against your own country, it’s in the name, but he wasn’t a citizen of Germany, so how can he have been accused of committing treason? Now, I can obviously imagine that the National Socialists who were presiding over his case were not very discerning in this matter, but what of the West German government when Johanne was written to about falsely claiming her widow’s pension? How can this not have been laughed out of court when the authorities became aware of it? In addition, however reprehensible it is that Oskar fought so hard to stay in the NSDAP, he was never charged with treason (or anything for that matter), let alone convicted, so what were the grounds on which his civil servant status was nullified and he was forbidden from working as a detective in 1943? A final problem is that, as part of the “agreement” when Lithuania returned the Memel Territory to Germany in March 1939, all agents on all sides were issued with an amnesty (Jenkis 2009, 76), according to which no one should have been prosecuted for their political behaviour prior to 1939 (Kurschat 1968, 209). I wonder if Johanne knew about that clause when she was arguing her case in the 50s and 60s. If she did, it is not recorded in the documents.

Of these three problems in assuming Oskar’s guilt, Johanne only emphasised the second, that he was not charged and not convicted because of a lack of evidence. The West German authorities seemed to keep coming back to the fact that his dismissal from office and from civil servant status was what counted, regardless of the reasons, and this wasn’t something that could just be overturned simply. She got there in the end, but that’s a story for another time. In the next post, I’ll focus on the contact and relations Oskar did have with the Lithuanian authorities in the interwar period, before I turn to the question of whether that meant he actually was on their pay roll in 1934-5.

References

Jakubavičienė, I. (2012) Der Neumann-Sass-Prozess 1934/35. Aus litauischer Sicht. Annaberger Annalen, 19, pp. 220-254.

Jenkis, H. (2009) Der Neumann-Sass-Kriegsgerichtsprozess in Kaunas 1934/1935

Aus deutscher Sicht. Annaberger Annalen, 17, pp. 53-103.

Kurschat, H. (1968) Das Buch vom Memelland. Verlag Werbedruck Köhler, Oldenburg.

Nikžentaitis, A. (1996) Germany and the Memel Germans in the 1930s (On the Basis of Trials of Lithuanian Agents before the Volksgerichtshof, 1934–45), The Historical Journal, 39, 3, pp. 771-783.